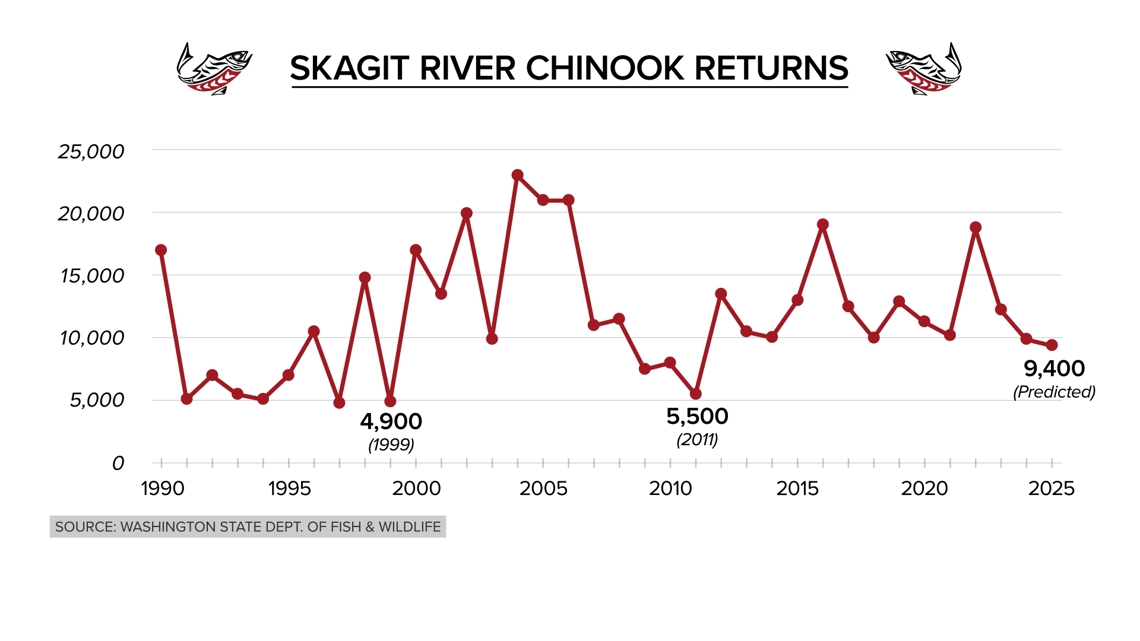

SKAGIT COUNTY, Wash. — The population of summer-fall Chinook salmon expected this year on Washington's Skagit River will be the lowest in nearly 15 years, dealing another devastating blow to Native American tribes whose culture and subsistence have depended on the fish for millennia.

The grim forecast means the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe will be permitted to harvest just 24 wild Chinook salmon this season — a stark contrast to the abundance their ancestors once knew.

"Hearing stories about the fish being so thick you could practically walk across them, to we're at a point now where if we catch 24 wilds, we have to shut down," said Chairman Nino Maltos of the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, who has been fishing these waters since age 6. "It's sad no matter how you look at it. It's devastating."

A Species in Crisis

Chinook salmon, also known as king salmon, form the bedrock of coastal Salish tribes' spiritual practices, subsistence and cultural identity. The species has been struggling for years, prompting the federal government to list Skagit Chinook on the Endangered Species List in 1999.

While tribes saw some improved years following that designation, this summer/fall predicted return represents the worst since 2011, according to data collected by the Washington State Dept. of Fish and Wildlife and tribal natural resource departments.

"Right now we're in dire straits. It doesn't get much worse than this," said Scott Schuyler, policy representative for Natural and Cultural Resource Department of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe. "The writing's on the wall. We need to do something different."

Century-Old Dams Block Recovery

The crisis comes as Seattle's century-old hydroelectric dams on the Skagit River undergo federal relicensing — a process that tribal leaders hope will help bring meaningful change to salmon recovery efforts.

In 1918, Seattle started construction of three dams on the Skagit River to generate electricity for the growing city. At the time, no tribal consultation occurred, and the dams were built without any fish passage systems.

Over the last four years, the KING 5 Investigators have exposed how Seattle got away with operating the only dams in the Northwest without a fish passage system.

For decades they peddled a theory that no tribe or government scientist believed: that fish couldn't swim up the steep terrain of the Skagit anyway, so investing in fish passage would be a waste of time and money.

To this day, the dams block 37% of the river's habitat from salmon and other fish species. Tribal biologists and other government scientists who study the river say this creates an insurmountable barrier to spawning grounds that sustained tribal communities for thousands of years.

A Breakthrough That Remains Incomplete

In 2023, Seattle City Light reversed decades of resistance and agreed to install fish passage systems at its Skagit River dams, a decision hailed by city officials as a step toward repairing environmental and cultural harm.

"This represents a piece of restorative justice here," said Debra Smith, then general manager of Seattle City Light, in April 2023. "What I see us doing here is saying 'we understand that we have impacted you and this was your land.’ And for this country, that has such a history with Native American people, such an ugly history, I think it’s really important.”

However, two years later, no final agreement has been signed.

This week, Seattle City Light informed federal regulators that all parties are in the "final stages of finalizing all settlement documents" and requested their third delay to allow all parties to “approve and execute the settlement agreement” by fall.

The May 27 letter to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission reveals the complexity of the negotiations, which involve three tribes and federal and state regulatory agencies. City Light cited "changes within the federal agencies under the current Administration" as one factor requiring additional time for the approval process.

Read the letter below:

A Generation Without Wild Salmon

The impact on tribal fishing traditions has been profound. There has not been a directed wild spring Chinook fishing season on the Skagit River since 1988 — 37 years ago, before Chairman Maltos was even born. The last summer/fall Chinook fishery occurred in 2009.

Today's tribal fishermen harvest only hatchery-reared Chinook, a far cry from the wild runs that once defined the river ecosystem and tribal way of life.

"We need this to happen. We need it as soon as possible," Maltos said, referring to the fish passage agreement. "We just want to stand firm on what's agreed to and get it done as absolutely as soon as possible."

For Schuyler and other tribal representatives, the urgency extends beyond cultural preservation to basic ecological survival.

"Right now we're taking care of the river," said Schuyler, who leads relicensing negotiations for the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe. "We have to and hopefully someday the river will take care of us again like it did for our ancestors."